Designing .NET Libraries with developers in mind

Working in a distributed system, one often turns to packaging common code into a reusable library. At its simplest, that could just be putting the classes we want to share in a library project, publishing it as a NuGet package and to be consumed where needed.

Job done, we have achieved reusability! But should we put more thought into it?

Yes! As a library developer, we have a responsibility to our users (other developers) to provide a library that is easy, and also desirable, to use. In this article we will walk through the creation and design of a library project, discussing things we should consider, and patterns we can adopt to create a simple, yet customizable, integration experience for our users.

- What Is The Purpose Of The Library?

- Creating the Project

- Open Source?

- Designing the library interface

- Extensibility

- Middleware

- Registration Builder

- Observability

- Configuration Options

- Versioning

- Test Package

- Summary

What Is The Purpose Of The Library?

Before we get started - what are we doing?

It may sound obvious, but especially when looking to share existing code across applications, we should make sure we are creating a module with a clear purpose.

If a library’s purpose is not well defined, over time it can become a mixed bag of unrelated classes, with an unwieldy collection of dependencies. So called “common” internal libraries like this are unfortunately all too, well, common. They force consumers to depend on packages they do not need, increasing the chance of version conflicts when building, and in some cases even restricting the version of .NET that must be targeted.

When designing a library, think in similar terms to designing a microservice; a library should have a well defined area of responsibility. With a library of such high cohesion, a more descriptive and appropriate name than “common” should be apparent.

For the purposes of this article, we will be creating a library for starting fire-and-forget background tasks. Note that the implementation is not appropriate for production scenarios, it is kept simple in order to focus on the design of the library.

With that clear purpose in mind, we can give our library an appropriate (and cool) name like BackgroundTaskr.

Creating the Project

First thing we need is a class library project to put the code.

So we’ll need to decide on the .NET version we are going to target. Here there is a trade off between compatibility, and availability of features. Given the current state of .NET, it can be a little confusing, but this article summarizes our choice down to 3 targets:

- .NET Standard 2.0 - to share code between .NET Framework and all other platforms.

- .NET Standard 2.1 - to share code between Mono, Xamarin, and .NET Core 3.x.

- .NET 5.0 - for code sharing moving forward. .NET 5.0 may seem like the right way to go in future, but there are many existing applications still using older flavours of .NET. We should not make upgrading the version of .NET a prerequisite to using our library, if it can be reasonably avoided.

So for our project, we’ll start off targeting .NET Standard 2.0, which is actually still the official guidance. We can revisit this decision if we find we need to use newer features, or wish to depend on other libraries which force our hand.

Open Source?

We may only wish to share our library within our own organisation, but even so, it is often a good exercise to explore if it would be suitable for open-sourcing.

Would the library we are creating expose application/organisation specific logic if it were open-sourced? If we have existing code, would we be happy to open-source it as is?

This thought process might help identify domain specific aspects of our library that would restrict its use in other applications, even within our own organisation. It could perhaps lead to a more general purpose solution, enabling future as yet unforeseen use cases. It may also highlight areas of improvement in existing code from a readability, structure, or test coverage perspective.

Say we already have an implementation of a background task factory we are going to use as a basis for our library, with the following task creation method:

public void CreateBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask)

{

Task.Run(async () =>

{

// Must use newly resolved dependencies in our background task to avoid accessing disposed scoped services.

using var scope = _serviceProvider.CreateScope();

try

{

await runTask(scope.ServiceProvider);

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

await scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<ISlackNotifier>().NotifyTaskFailure(name, exception);

}

});

}Here we are notifying slack on failure of a task, which is obviously an organisational (if not application) specific piece of logic. If open sourcing, we would certainly not want such logic to be included in our library. Even within our own organisation, there could be use cases where we may not want that behaviour for all tasks. So in our library we will not include this behaviour, but instead design for extensibility, allowing for such behaviours to be injected.

Designing the library interface

Usage Interface

Given good developers test their code, we can assume users of our library will want to code against an interface for creating background tasks, to allow for injecting a different implementation in unit tests. Exposing our task factory as an interface also enables useful patterns like decorators, giving the potential for some extensibility without any effort on our part.

So we’ll define our interface as:

public interface IBackgroundTaskr

{

void CreateBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask);

}And for reference, the initial implementation:

internal class BackgroundTaskFactory : IBackgroundTaskr

{

private readonly IServiceProvider _serviceProvider;

public BackgroundTaskFactory(IServiceProvider serviceProvider)

{

_serviceProvider = serviceProvider;

}

public void CreateBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask)

{

Task.Run(async () =>

{

try

{

// Must use newly resolved dependencies in our background task to avoid accessing disposed scoped services.

using var scope = _serviceProvider.CreateScope();

await runTask(scope.ServiceProvider);

}

catch

{

}

});

}

}Minimal Surface Area

Note that we keep the above class internal, as we do not expect it to be instantiated directly (see next section…). This is good practice in general for any class that is not required to be directly referenced when using the library.

Any public type in our library that we wish to change, could result in a compile time break for consumers when upgrading. Therefore we should minimise the surface area of the library interface as much as is practicable, to allow us to safely make changes to the implementation, knowing no consumers are referencing it.

So as we build out our library, we’ll mark each new type as internal, unless or until we find a need to make it public.

Registration Interface

A good library works out of the box, with minimal to no configuration. An intuitive interface, with little effort to start using it, lowers the barrier to adoption.

Many official .NET libraries make use of the built in dependency injection support, and developers are accustomed to registering libraries with extension methods on the IServiceCollection. So we’ll design our library to be registered in a similarly intuitive way:

services.AddBackgroundTaskr();Initially implemented as such:

namespace Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection

{

public static class BackgroundTaskrServiceCollectionExtensions

{

public static void AddBackgroundTaskr(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.TryAddSingleton<IBackgroundTaskr, BackgroundTaskFactory>();

}

}

}There are a couple of things to note here:

- We put this class in the

Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection namespace, as with other libraries’ registration methods, making the method more easily discoverable by intellisense. - We use

TryAddSingletonwhich prevents multiple registrations if our method is called multiple times by mistake.

We now have a basic version of our library coded up that we could publish, but remember we needed a way to inject custom behaviour for our slack notification use case…

Extensibility

Libraries often need to be extensible, allowing developers to tailor the behaviour to their specific use case. There are a couple of patterns in the .NET ecosystem that we can use to allow our libraries behaviour to be customized:

- Middleware - allowing custom code to be executed for all invocations of an operation, often configured using a…

- Registration Builder - for example, adding extra or custom behaviours,

- Configuration Options - for example, configuring settings or toggling features on/off, but also can be used to inject behaviour via funcs/actions.

In practice, many libraries will use a combination of the above approaches, and so will we…

Middleware

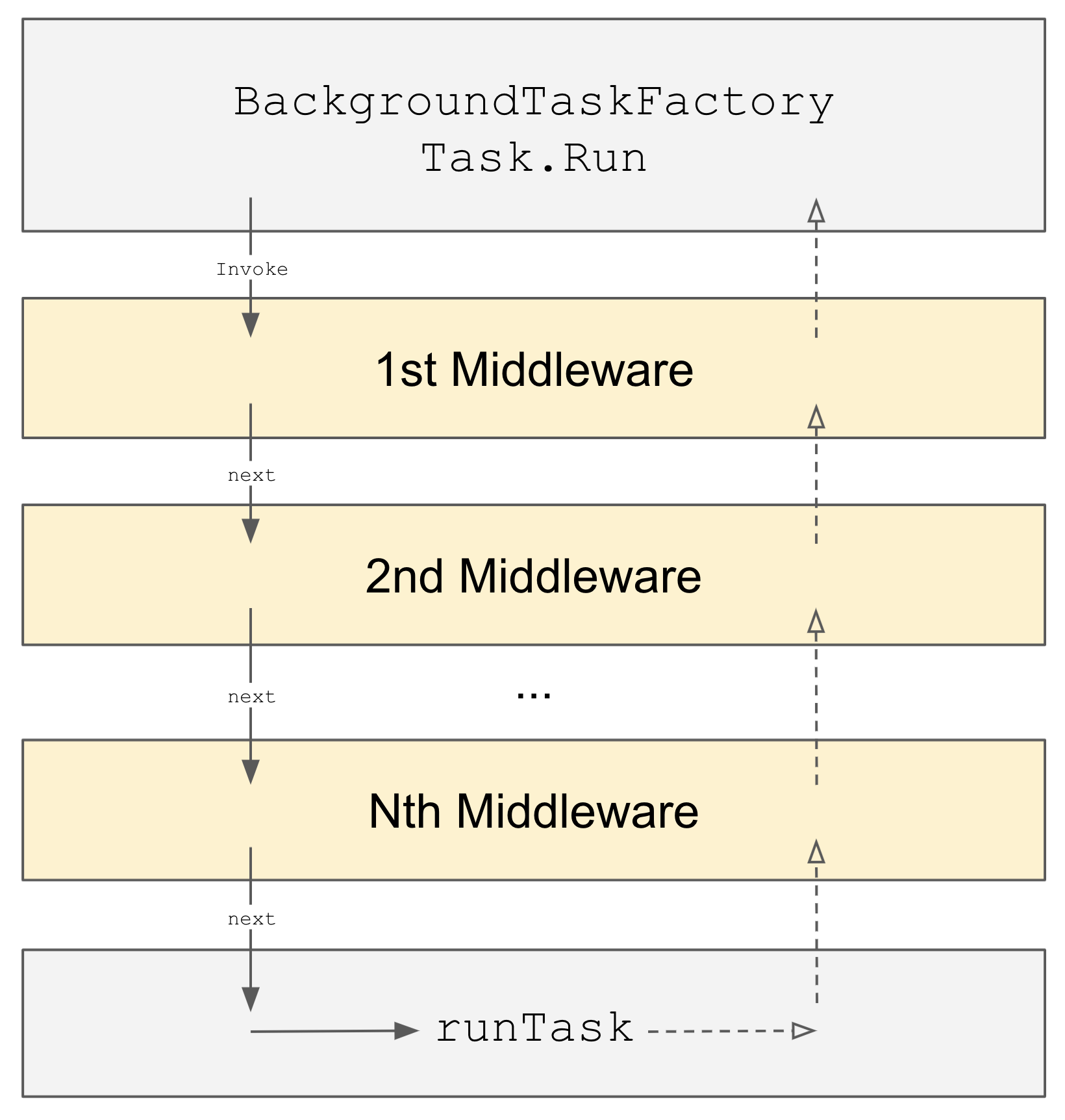

Middleware is a powerful capability that allows any custom behaviour to wrap an operation, like a decorator. It is a concept that should be familiar to many developers, so we will adopt the same pattern in our library. Essentially we would need to call any middlewares in a pipeline around the running of background tasks:

Firstly let’s define a middleware interface, that is passed context about the current operation, and a next func to call the next part of the pipeline:

public interface IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware

{

public Task OnNext(string name, Func<Task> next);

}Note the only context info we have is the name of the task, but in general we’d expect more useful information to be made available in middleware. For example, if we had some state we passed to running tasks, we would make that available to inspect or modify in the middleware.

We will need to chain multiple middlewares together, so we will define a class to do so. As illustrated above, each middleware needs to be invoked with a next func which invokes the next middleware in the chain, or runs the background task if it is the innermost middleware. If we knew there were always 2 middleware, an implementation might look something like this:

internal sealed class MiddlewareInvoker : IMiddlewareInvoker

{

private readonly IReadOnlyList<IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware> _middlewares;

public MiddlewareInvoker(IEnumerable<IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware> middlewares)

{

_middlewares = middlewares.ToList();

}

public Task InvokeAsync(string name, Func<Task> runTask) =>

_middlewares[0].OnNext(name, () => _middlewares[1].OnNext(name, runTask));

}Now we’ve figured out a simple case, we can see how to extrapolate to the general case, using LINQ to do the heavy lifting: reversing the list and using the Aggregate method to build our middleware pipeline from the innermost layer outwards:

internal sealed class MiddlewareInvoker : IMiddlewareInvoker

{

private readonly IReadOnlyList<IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware> _middlewaresInReverse;

public MiddlewareInvoker(IEnumerable<IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware> middlewares)

{

_middlewaresInReverse = middlewares.Reverse().ToList();

}

public Task InvokeAsync(string name, Func<Task> runTask) =>

_middlewaresInReverse.Aggregate(runTask, (next, middleware) => () => middleware.OnNext(name, next))();

}Note that we will leverage the fact that .NET dependency injection automatically resolves all registered T (in order of registration) when injecting an IEnumerable<T>.

We now must register the MiddlewareInvoker in our registration method, so we can resolve and use it:

services.TryAddScoped<IMiddlewareInvoker, MiddlewareInvoker>();Then we update our BackgroundTaskFactory to use it, by adding tweaking how we invoke the runTask func as such:

var invoker = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<IMiddlewareInvoker>();

await invoker.InvokeAsync(name, () => runTask(scope.ServiceProvider));Registration Builder

Now we need a way of registering middlewares, and for that we will use the builder pattern. Firstly, we’ll define an interface for our builder:

public interface IBackgroundTaskrBuilder

{

public IServiceCollection Services { get; }

}All we really need here is a reference to the IServiceCollection so we can add more registrations to it. If we had a more complicated library where we could add more than one instance of something (e.g. HttpClient) we’d likely also have a Name property here to indicate the instance the builder is related to.

Note that we also do not define any methods on this interface, instead all builder functionality will be provided through extension methods. Since adding a method to an interface would be a compile time break, using extension methods here allows us to add more functionality in future without a breaking change.

So we define a few extension methods to allow registering middlewares as such:

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder UsingMiddleware(

this IBackgroundTaskrBuilder builder,

Func<IServiceProvider, IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware> resolveMiddleware)

{

builder.Services.AddScoped<IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware>(resolveMiddleware);

return builder;

}

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder UsingMiddleware<TMiddleware>(this IBackgroundTaskrBuilder builder)

where TMiddleware : IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware =>

builder.UsingMiddleware(x => x.GetRequiredService<TMiddleware>());

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder UsingMiddleware(

this IBackgroundTaskrBuilder builder,

Func<string, Func<Task>, Task> onNext) => builder.UsingMiddleware(_ => new FuncMiddleware(onNext));

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder UsingMiddleware(

this IBackgroundTaskrBuilder builder,

Func<IServiceProvider, string, Func<Task>, Task> onNext) =>

builder.UsingMiddleware(s => new FuncMiddleware((name, next) => onNext(s, name, next)));

internal class FuncMiddleware : IBackgroundTaskrMiddleware

{

private readonly Func<string, Func<Task>, Task> _onNext;

public FuncMiddleware(Func<string, Func<Task>, Task> onNext)

{

_onNext = onNext;

}

public Task OnNext(string name, Func<Task> next) => _onNext(name, next);

}These allow for multiple ways of registering middlewares, respectively:

- resolving/creating the instance explicitly,

- providing just the implementation type to be resolved,

- or providing an inline func defining the behaviour of the middleware (with or without resolving dependencies).

Note each builder method returns the builder, to allow chaining. We must also return a builder from the initial registration method, so it can be used:

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder AddBackgroundTaskr(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.TryAddSingleton<IBackgroundTaskr, BackgroundTaskFactory>();

services.TryAddScoped<IMiddlewareInvoker, MiddlewareInvoker>();

return new BackgroundTaskrBuilder(services);

}

internal class BackgroundTaskrBuilder : IBackgroundTaskrBuilder

{

public BackgroundTaskrBuilder(IServiceCollection services) => Services = services;

public IServiceCollection Services { get; }

}We can now specify our application specific slack notification in a custom middleware when registering the library, for example:

services.AddBackgroundTaskr()

.UsingMiddleware(async (serviceProvider, name, next) =>

{

try

{

await next();

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

await serviceProvider.GetRequiredService<ISlackNotifier>().NotifyTaskFailure(name, exception);

}

});If this turns out to be something we need in multiple services, we could publish a separate internal library with an extension method on the IBackgroundTaskrBuilder for easy registering of such a middleware. (See this commit for an example implementation.)

Observability

Running a reliable production system requires us to be able to understand the behaviour of the live system, and detect and analyze failures. When writing code, we should think about how we will be able to ascertain what the code is doing when running in production. The key to this is having our code produce signals at key events (at a minimum: at the beginning and end of an operation, and on errors), with high dimensionality and high cardinality.

Looking at our existing BackgroundTaskFactory implementation, right now if we ran this in production, we’d have no way to know when a task was triggered, run, failed etc., let alone start to understand the reason for any failures. So let’s look at ways we can make our library observable out of the box.

OpenTelemetry

OpenTelemetry has been designed as a language/platform agnostic standard for observability, with “the inspiration of the project [being] to make every library and application observable out of the box”. This sounds like it is exactly what we want.

The .NET implementation of the OpenTelemetry API uses the existing Activity to represent an OpenTelemetry Span, which essentially represents the current operation (e.g. HTTP request). Because of this, some OpenTelemetry concepts have different terminology in the .NET implementation, for example:

| OpenTelemetry Terminology | .NET Terminology |

|---|---|

| Tracer | ActivitySource |

| Span | Activity |

| Attribute | Tag |

Many of the existing official .NET libraries (e.g. HttpClient) have separate packages to add OpenTelemetry instrumentation, but the guidance for new libraries is to bake the instrumentation in, without the need for a separate package. So we will do accordingly with our library.

We have two operations to instrument in our library; the creation and running of the background task. In order to create activities for them, we will need an ActivitySource:

private static ActivitySource ActivitySource { get; } = new ActivitySource("Haydabase.BackgroundTaskr");We can then instrument our CreateBackgroundTask method as such:

public void CreateBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask)

{

using var createActivity = ActivitySource.StartActivity(

$"Create BackgroundTask: {name}",

ActivityKind.Internal,

default(ActivityContext),

new Dictionary<string, object?> {["backgroundtaskr.name"] = name});

var propagationContext = createActivity?.Context ?? Activity.Current?.Context ?? default(ActivityContext);

Task.Run(async () =>

{

using var runActivity = ActivitySource.StartActivity(

$"Run BackgroundTask {name}",

ActivityKind.Internal,

propagationContext,

new Dictionary<string, object?> {["backgroundtaskr.name"] = name});

try

{

using var scope = _serviceProvider.CreateScope();

var invoker = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<IMiddlewareInvoker>();

await invoker.InvokeAsync(name, () => runTask(scope.ServiceProvider));

runActivity?.SetStatus(Status.Ok);

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

runActivity?.RecordException(exception);

runActivity?.SetStatus(Status.Error);

}

});

createActivity?.SetStatus(Status.Ok);

}For more information on how to the Activity API should be used, see the official documentation, but here are some things to note:

StartActivitymay returnnull, if no listeners are registered on theActivitySource(typically if the application has not set up any exporters for our telemetry data), hence the use of the null-conditional operator when accessing theActivityproperties/methods.- We explicitly propagate the

createActivity’s context when creatingrunActivity. This is not strictly required here, as any existingActivity’s context is automatically used as the parent on creation of a newActivity. If we’d implemented this library by storing jobs in a database to ensure resiliency to service restarts, we would also have to store the context in order to propagate it when fetching the job out of the database. See the official documentation’s example code for how to inject and extract context using the Propagators API.

In order for users of OpenTelemetry to collect traces from our library, they must use the AddSource method of the TracerProviderBuilder in their setup. Given we want configuring our library to feel intuitive to use, we’ll add a convenience extension method for adding the instrumentation, using the same semantics as other instrumentations (e.g. AspNetCore):

services.AddOpenTelemetryTracing(

x => x

.SetResourceBuilder(ResourceBuilder.CreateDefault().AddService("BackgroundTaskr.DemoApp"))

.AddBackgroundTaskrInstrumentation()

.AddAspNetCoreInstrumentation()

.AddConsoleExporter()

);Simply implemented as such:

namespace OpenTelemetry.Trace

{

public static class TracerProviderBuilderExtensions

{

public static TracerProviderBuilder AddBackgroundTaskrInstrumentation(this TracerProviderBuilder builder) =>

builder.AddSource("Haydabase.BackgroundTaskr");

}

}In our instrumentation, we set a single tag on creation of each Activity, using the only information we have about the task; the name. Additional tags can be added to at any point during the operation, enabling enrichment of telemetry data to help our users achieve the high dimensionality and cardinality we were looking for. There are already methods for enriching the task running Activity; either in a middleware, or in the task itself, by accessing Activity.Current. There aren’t, however, any methods for enriching the task creation Activity. We can again take inspiration from other instrumentation libraries to add such a capability…

Configuration Options

Most of the official .NET instrumentation libraries provide a mechanism for enriching the activities they instrument via the Options pattern (e.g. HttpClient). We will use the same approach in our library. Firstly we’ll define an options class:

public class BackgroundTaskrOptions

{

public Action<Activity, string, object>? EnrichCreate { get; set; }

public Action<Activity, string, object>? EnrichRun { get; set; }

}The standard mechanism for configuring options that developers will expect, is via a configure Action on the registration method, so we’ll update ours with some overloads allowing that:

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder AddBackgroundTaskr(this IServiceCollection services,

Action<IServiceProvider, BackgroundTaskrOptions> configure)

{

services.AddTransient<IConfigureOptions<BackgroundTaskrOptions>>(serviceProvider =>

new ConfigureOptions<BackgroundTaskrOptions>(options => configure(serviceProvider, options)));

services.TryAddSingleton<IBackgroundTaskr, BackgroundTaskFactory>();

services.TryAddScoped<IMiddlewareInvoker, MiddlewareInvoker>();

return new BackgroundTaskrBuilder(services);

}

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder AddBackgroundTaskr(this IServiceCollection services,

Action<BackgroundTaskrOptions> configure) =>

services.AddBackgroundTaskr((_, options) => configure(options));

public static IBackgroundTaskrBuilder AddBackgroundTaskr(this IServiceCollection services) =>

services.AddBackgroundTaskr(_ => { });As with previous extensions, we provide multiple overloads for convenience of consumers, respectively:

- one to allow resolving dependencies for the enrichment,

- another simpler configuration action if no dependencies are required,

- and finally leaving the original overload for if no configuration is desired.

In order to use the configured enrichment actions, we must inject an IOptions<> instance to our BackgroundTaskFactory:

internal class BackgroundTaskFactory : IBackgroundTaskr

{

private static ActivitySource ActivitySource { get; } = new ActivitySource("Haydabase.BackgroundTaskr");

private readonly IServiceProvider _serviceProvider;

private readonly IOptions<BackgroundTaskrOptions> _options;

public BackgroundTaskFactory(IServiceProvider serviceProvider, IOptions<BackgroundTaskrOptions> options)

{

_serviceProvider = serviceProvider;

_options = options;

}

public void CreateBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask)

{

var options = _options.Value;

using var createActivity = ActivitySource.StartActivity(

$"Create BackgroundTask: {name}",

ActivityKind.Internal,

default(ActivityContext),

new Dictionary<string, object?> {["backgroundtaskr.name"] = name});

options.EnrichCreate?.InvokeSafe(createActivity, "OnStartActivity", name);

var propagationContext = createActivity?.Context ?? Activity.Current?.Context ?? default(ActivityContext);

Task.Run(async () =>

{

using var runActivity = ActivitySource.StartActivity(

$"Run BackgroundTask {name}",

ActivityKind.Internal,

propagationContext,

new Dictionary<string, object?> {["backgroundtaskr.name"] = name});

options.EnrichRun?.InvokeSafe(runActivity, "OnStartActivity", name);

try

{

// Must use newly resolved dependencies in our background task to avoid accessing disposed scoped services.

using var scope = _serviceProvider.CreateScope();

var invoker = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<IMiddlewareInvoker>();

await invoker.InvokeAsync(name, () => runTask(scope.ServiceProvider));

runActivity?.SetStatus(Status.Ok);

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

runActivity?.RecordException(exception);

runActivity?.SetStatus(Status.Error);

options.EnrichRun?.InvokeSafe(runActivity, "OnException", exception);

}

finally

{

options.EnrichRun?.InvokeSafe(runActivity, "OnStopActivity", name);

}

});

createActivity?.SetStatus(Status.Ok);

options.EnrichCreate?.InvokeSafe(createActivity, "OnStopActivity", name);

}

}Note that each access of IOptions<>.Value evaluates all registered configuration actions, so we only call it once per task we create.

Also note that we are calling a custom InvokeSafe extension method on the enrich actions. This is simply to ensure we only call the action if the Activity is not null, and that we swallow any exceptions occurring during enrichment. The OpenTelemetry error handling specification explicitly mentions that instrumentions should not throw unhandled exceptions, and particularly must take care when accepting external callbacks, as we are here.

Now users of our library can add custom enrichment while registering as such:

services.AddBackgroundTaskr(options =>

{

options.EnrichCreate = (activity, eventName, rawObject) =>

{

switch (eventName)

{

case "OnStartActivity" when rawObject is string taskName:

{

activity.SetTag("custom_task_name", taskName);

break;

}

case "OnStopActivity" when rawObject is string taskName:

{

activity.SetTag("total_milliseconds", activity.Duration.TotalMilliseconds);

break;

}

}

};

options.EnrichRun = (activity, eventName, rawObject) =>

{

switch (eventName)

{

case "OnStartActivity" when rawObject is string taskName:

{

activity.SetTag("custom_task_name", taskName);

break;

}

case "OnException" when rawObject is Exception exception:

{

activity.SetTag("stack_trace", exception.StackTrace);

break;

}

case "OnStopActivity" when rawObject is string taskName:

{

activity.SetTag("total_milliseconds", activity.Duration.TotalMilliseconds);

break;

}

}

};

});Hopefully we can now see how we could easily add more configuration settings/toggles to our options class to enable further custom behaviours.

Versioning

Inevitably libraries evolve over time, as our library has during the previous few sections, to include new features, or fix bugs. So we must consider versioning…

SemVer is the de facto standard for versioning libraries, as recommended in the .NET guidelines. This enables developers to easily infer the level of changes between versions, most crucially which versions are backwards compatible and so can be safely upgraded to, and which may require changes in order to upgrade.

Even when using SemVer, thought must be put into which is the appropriate next version. Whilst techniques like Conventional Commits can help keep track of changes, developers still need to mark their changes appropriately. So it is vital that any developer maintaining a library be aware of what qualifies as a breaking change. For example, breaking changes do not have to be compilation errors; they can equally be changes in behaviour when coding against the same interface.

Where possible, we should provide a mechanism to opt-in to new/different behaviour rather than making a breaking change. For example, imagine we wanted to update our library so that it retries failed tasks. This could have undesirable consequences for users that may reasonably not have coded their tasks to handle being retried. We have a couple of simple ways that we have seen to make this update backwards compatible:

- Add a boolean flag to our

BackgroundTaskrOptionsclass to control if the retry behaviour is enabled (falseby default) - Add an

AddRetriesmethod to our builder, which could have the same effect, but with its own options for configuring numbers of attempts, back-off policies etc. It could even simply add a middleware which implements the retries.

Test Package

Coming full circle to when we first started designing our library, we mentioned facilitating unit testing as a reason for exposing our libraries functionality through an interface. Doing so enables our consumers to mock-out (or implement themselves) the interface in unit tests. Sometimes simulating the functionality of a library interface is not straightforward, so it is worth considering providing test implementations, in order to ease the testing setup burden for our consumers.

When thinking about a test implementation, it helps to have example code that uses our library, that we can try writing tests for. This helps us think about what we’d want from a consumer’s point of view, in order to easily test classes that use our library’s interfaces.

In the case of our library, a consumer would likely want an easy way to:

- setup the dependencies to be resolved from an

IServiceProviderwhen running tasks, - determine if tasks have run to completion, or failed.

So we’ll create a test implementation of

IBackgroundTaskrthat can take care of these concerns.

Addressing the first concern, our test implementation could provide a constructor that allows registering dependencies with an IServiceCollection. This could look something like:

public SynchronousBackgroundTaskr(Action<IServiceCollection> registerServices)

{

var services = new ServiceCollection();

registerServices(services);

_serviceProvider = services.BuildServiceProvider();

}Now consumer test setup can be fairly concise, for example:

var backgroundTaskr = new SynchronousBackgroundTaskr(

services => services

.AddScoped<IDelayer, FakeDelayer>()

);With regards to asserting on the running and outcome of the tasks, this is more complex when the tasks are run in the background, as we’d need a way to wait for them to finish. As may already be obvious from the above snippets, we can simplify this problem by running tasks synchronously in our test implementation. Consumers are unlikely to require the tasks actually run in the background for unit tests, since time consuming dependencies themselves can be mocked. If tasks run synchronously, we can simply add a list of invocations that can be checked at the end of a test run. So our test implementation will look something like this:

void IBackgroundTaskr.CreateBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask) =>

RunBackgroundTask(name, runTask).Wait();

private async Task RunBackgroundTask(string name, Func<IServiceProvider, Task> runTask)

{

try

{

using var scope = _serviceProvider.CreateScope();

await runTask(scope.ServiceProvider);

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

_invocations.Add(new Invocation(name, exception));

return;

}

_invocations.Add(new Invocation(name, null));

}

private readonly List<Invocation> _invocations = new List<Invocation>();

public IReadOnlyList<Invocation> Invocations => _invocations.AsReadOnly();

public class Invocation

{

public Invocation(string taskName, Exception? exception)

{

TaskName = taskName;

Exception = exception;

}

public string TaskName { get; }

public Exception? Exception { get; }

}There are a couple of choices here to note:

- We explicitly implement the

IBackgroundTaskr.CreateBackgroundTaskmethod, which prevents it being called without some additional effort in test code. The reason for doing so is to separate the methods/properties of the test implementation that are for testing (in this case the constructors +Invocations), for those intended to be called in production code via the public interface. - We do not allow the

_invocationlist to be modified outside the class, to ensure there is no way for it to be populated other than a task running.

Now consumer test assertions can also be fairly concise, for example if using FluentAssertions:

var invocation = backgroundTaskr.Invocations.Should().ContainSingle().Subject;

invocation.TaskName.Should().Be(name);

invocation.Exception.Should().BeNull();When publishing our test implementation, we should do so in a separate BackgroundTaskr.Testing NuGet package. As it is intended to only be consumed in test projects, we keep it separate to reduce the risk of accidental usage in production code.

Summary

We have seen how we can design a .NET library that is intuitive to configure, use, extend, and test, as well as easy to adopt and maintain by:

- Ensuring it has a well defined raison d’être, and avoiding unnecessary dependencies

- Designing with an open-source attitude, even if we may not be open-sourcing

- Choosing a .NET target as wide reaching as possible, considering required features

- Creating types as

internalby default - Using concepts developers will be familiar with from other libraries:

- Middleware

- Builders

- Options

- Providing Observability out of the box with OpenTelemetry

- Versioning with SemVer and avoiding breaking changes where practicable

- Providing a

*.Testingpackage, where useful, to elevate some test complexities

Further Reading

This is by no means an exhaustive list of concerns, omitting other important aspects like documentation, CI/CD, testing etc, so here are some links covering other relevant topics:

- Guidance for library authors - .NET Blog

- Document your C## code with XML comments - .NET Guidelines

- How To Build & Publish NuGet Packages With GitHub Actions - jamescroft.co.uk blog

- Level up your .NET libraries - benfoster.io blog